Have you kept a New Year’s resolution? I don’t believe I ever have. That’s probably a good reason to avoid them.

Yet, there’s something undeniably hopeful about New Year’s. In the dead of winter, it’s a moment of renewal. A time to pause and reflect. A time to contemplate the future.

History often shocks me. I was intent to have Sumner and Madeleine from A Keepsake Love celebrate 1925 New Year’s Eve to Auld Lang Syne. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that wasn’t a “thing.”

Auld Lang Syne is a Scottish folk song often attributed to Robert Burns. The version we’re familiar with accidentally became associated with New Year’s during a national radio broadcast in 1929. Guy Lombardo played the piece shortly after midnight and our tradition was born.

The celebration of New Year’s has a convoluted history. The Roman emperor Julius Caesar originally established the holiday on January 1. January is named for the Roman god Janus who had two faces, one looking forward and one backward. Roman pagans celebrated by indulging in drunken orgies meant to reenact the chaos of their world before it was put in order by their gods. Could New Year’s association with drink stem from this time?

By the early medieval period, Christians celebrated Annunciation Day as the start of the new year. March 25 was when the angel Gabriel announced to Mary that she was destined to be the mother of Jesus.

For mostly political reasons, William the Conqueror returned New Year’s to January 1. He wished to associate Christmas with his coronation and commemorate Jesus’ circumcision as the start of the new year. Unfortunately for William, his tactics failed and Christians returned New Year’s celebrations to March 25.

It was about five hundred years later that Pope Gregory XIII put an end to the Julian calendar. In 1582, the New Year began on the first day of the month of Janus just as it was calendared by early pagans.

How about our famous New Year’s ball drop? Where did that tradition originate? Time balls were used in harbors as long ago as 1829 in Portsmouth. Since it was impossible to see the hands of a clock from any distance, large balls were positioned high enough that seafaring captains could tell the time. Balls were dropped exactly at noon, but weather often ruined the timing. Eventually the telegraph transmitted time more accurately.

When New York enacted a fireworks ban, the New York Times had to abandon their annual New Year’s fireworks display. Instead, owner Adolph Ochs constructed a 700-pound iron and wood ball and had it lowered from the flagpole positioned on top of Times Tower. Thus the obsolete method of telling time became our beloved holiday tradition on New Year’s Eve, 1907.

Let’s return to our original and most ancient New Year’s tradition—the resolution. Babylonians celebrated a festival called Akitu over 4,000 years ago. They pledged their loyalty to their king, promised to pay debts and return borrowed items.

Later, Romans made resolutions on New Year’s as a rite of passage. We’re back to Janus, that god who looked to the future and the past. Romans pledged to be good citizens and gave gifts meant as lucky omens for the coming year.

Finally, early Christians atoned for sins as part of formalized worship services held on New Year’s Eve.

As New Year’s has become more secular, resolutions are rarely about the betterment of society and instead focus on individual goals such as losing weight, improving finances and reducing stress.

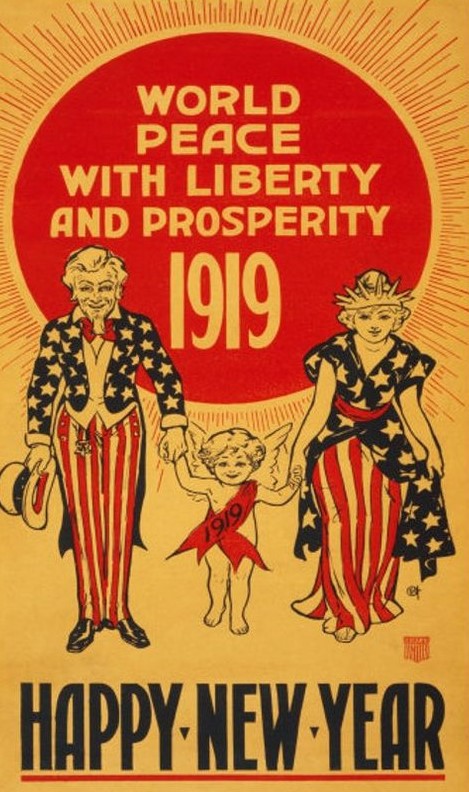

Whether or not you make a 2022 resolution, New Year’s is a great opportunity to honor the passing of time, reflect on the past and appreciate the chance to make a fresh start.

Great content! Keep up the good work!